Last month, a new kind of monument quietly but powerfully emerged over the busy intersection of 9th and Broadway in Downtown Los Angeles. Instead of a celebrity endorsement or tech startup promotion, the billboard space now serves as a living, breathing canvas.

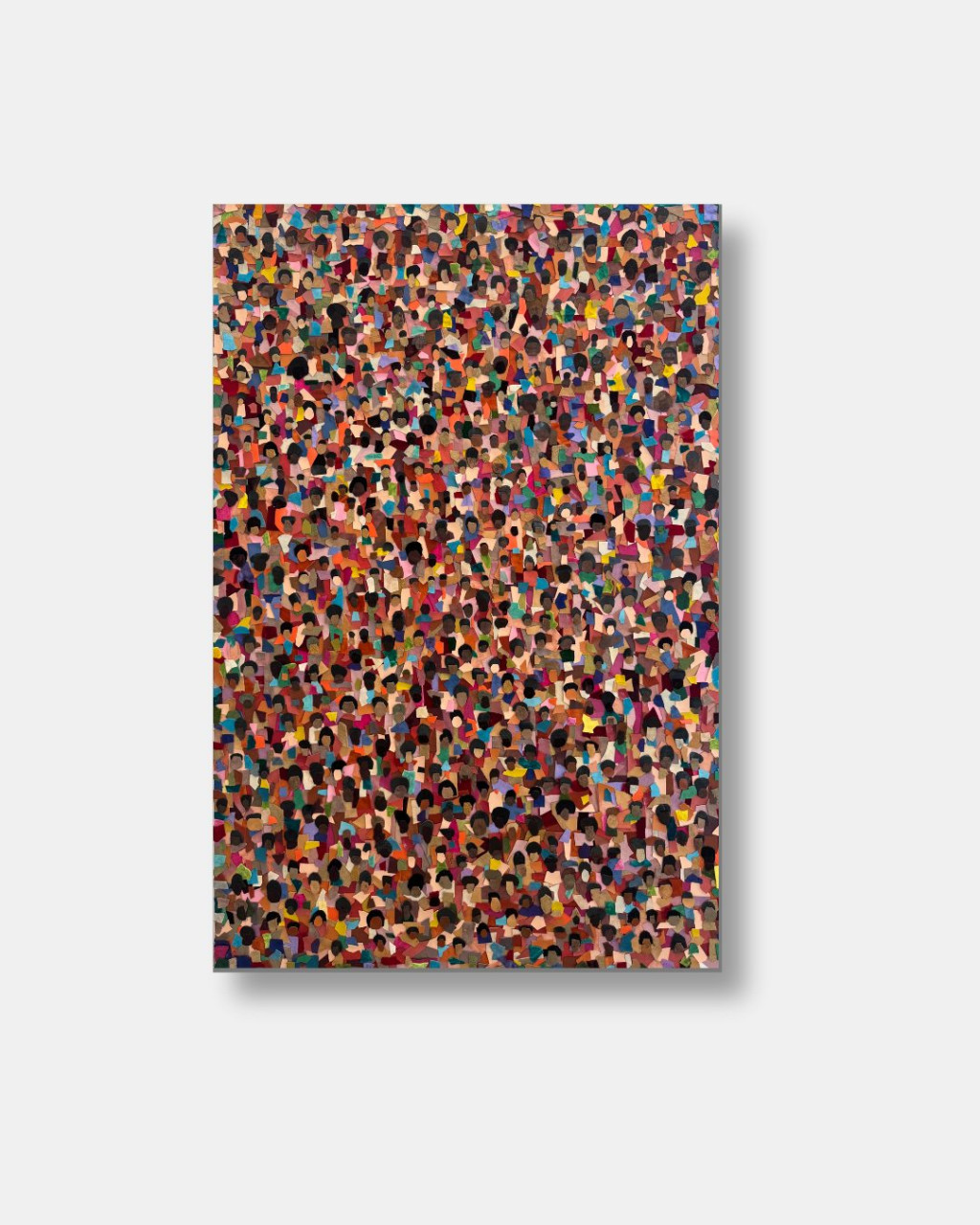

Towering above commuters and creatives is a vibrant work titled When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised, created by LA-based multidisciplinary artist Doug Hickman Jr.

Selected as part of The Things That Bind Us, a public art curation by Nakeyta Moore and presented by ArtLoudLA in collaboration with SaveArtSpace, Hickman’s piece isn’t just art, it’s memory, homage, and protest all stitched into one.

It’s rooted in the aesthetics and soul of Questlove’s 2021 documentary Summer of Soul (Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), a film that unearthed long-lost footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. But Hickman takes that inspiration a step further, using salvaged fabrics sourced from LA’s Fashion District, just blocks away from the billboard site, to literally sew a piece of the city into his work.

Hickman is no stranger to this kind of visual storytelling. His creative practice lives at the intersection of fashion, architecture, and cultural narrative, and this latest piece feels like a full-circle moment. The billboard stands as both a personal and communal call to remembrance.

We caught up with Hickman just days after the reveal of his powerful Downtown LA billboard installation, where he opened up about the personal connection behind When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised, how salvaged fabric became his storytelling tool, and why honoring Black history through art is more vital now than ever.

QG: What was the spark that led you to create “When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised”? Was it a particular moment in Summer of Soul or something more personal?

DH: No, not a particular moment, but yes, very much so personal. 5 minutes into the film, I was emotionally and spiritually invested in Summer of Soul. From living in the same area over a decade ago, where the Harlem Cultural Festival took place, to being fascinated with stories of Black American History. Also, having a background in music and fashion deepened my love for the film.

QG: How did you approach using salvaged fabrics from LA’s Fashion District as part of your storytelling?

DH: I’ve always been an avid believer of constructing and creating something out of nothing, being resourceful. I do my best work from that. My works primarily consist of Black American moments in History, so utilizing salvaged fabrics ties perfectly with my storytelling.

QG: You’ve described this piece as a “personal visual” in Questlove’s documentary. How did you translate the energy, joy, and resistance of the Harlem Cultural Festival into your artistic language?

DH: Through the film’s color palettes, paired with the utilization of instruments on stage, which led to the movement of the crowd. Seeing the various wardrobe color hues and shades of brown skin intertwined. When constructing a piece of work, I’m often inspired by huge stained glass windows of churches. For me, being reared in church, the significance and beauty through stained glass personally brings me back to a time of jubilation, cultural energy, and community love.

QG: What does it mean for you to see your piece on a billboard in the heart of Downtown LA?

DH: It’s still kind of a shock. Waking up in the morning and going about my day, knowing that my work is being displayed downtown is pretty wild. In a good way, though. I’m completely overwhelmed with gratitude.

QG: The piece is a centerpiece of The Things That Bind Us, a curation by Nakeyta Moore. How did that curatorial vision challenge or deepen the way you approached your work?

DH: The curatorial vision challenged me to think more intentionally about how my work resides in a larger conversation, both visually and conceptually. It deepened my process by motivating me to connect my personal themes to bigger cultural or historical contexts, which added more depth and clarity to my message.

QG: What is material memory, and why is it important in today’s cultural climate?

DH: Material memory is the idea that physical materials hold and reflect traces of their history and cultural significance. Material memory is important because it preserves cultural identity and uncovers hidden and erased histories, much like what the government is attempting to do now. Also, sustainability and ethical materials are one of the direct responses to climate change.

QG: This work feels both rooted in history and urgently present. How do you see your role as an artist in today’s social and political moment?

DH: My role is to introduce historical moments with visual storytelling and continue conversations of black history beyond my works of art. With today’s society being fueled by visual learning and the effort to erase black history, I’ve made a choice to step into a position of helping to keep these stories alive.

QG: You’ve talked about expanding into immersive installations, international shows, and more. What kind of spaces or collaborations are you dreaming about next?

DH: I would love to collaborate and partner with programs geared toward visual storytelling and Black history, both domestically and globally. Working with school districts around the country to create art programs for youth is a huge goal of mine. Also, forming these same projects and initiatives back in my hometown, Chicago, where there is much hidden and suppressed history.

QG: What does visibility mean to you right now, at this stage in your career?

DH: Having over 17 years as a creative under my belt, the visibility of giving back to my community means the most, and the world to me. My goal has always been to reach a larger community and to connect and learn about black history through visuals.

QG: Finally, if someone is walking down 9th and Broadway and looks up at your piece, what do you hope they feel in that moment?

DH: Heavily inspired.

Order prints of Doug Hickman’s When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised here.

Photo Credit: Jon Dailey