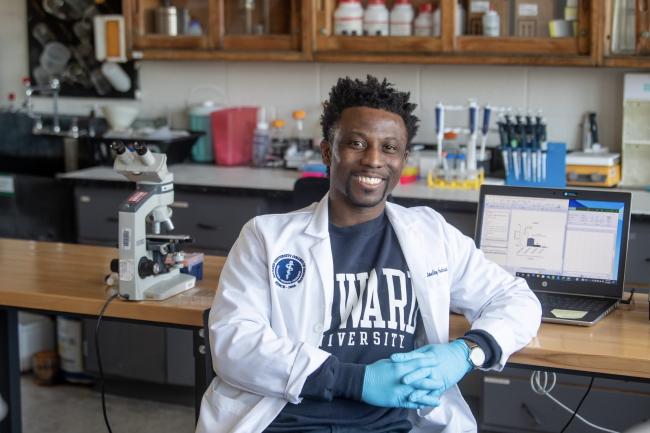

Howard University College of Medicine professor Stanley Andrisse, Ph.D., is living proof that a person’s past does not have to dictate their future.

Once labeled a “career criminal” before the age of 21, Andrisse now stands as a tenured professor at the nation’s only R1-designated HBCU, a milestone he describes as both deeply personal and powerfully symbolic.

“My story represents both possibility and responsibility,” he says in a feature posted on Howard University’s website. “It’s proof that redemption is real — that someone who was once written off as a ‘career criminal’ can stand in front of classrooms, lead research, and shape the next generation of scientists.” To his knowledge, he is the first formerly incarcerated Black man in U.S. history to earn tenure at a medical school.

But Andrisse’s journey began far from academic lecture halls.

Andrisse grew up in Ferguson, Missouri, a community marked by structural inequities and policing practices that defined national headlines decades later. He remembers being viewed not as a teenager, but as a threat. Those early experiences shaped him into an educator who leads with empathy.

“I know what it feels like to be dismissed, underestimated, and denied opportunity,” he says. “As a mentor, I try to be the voice I needed back then. I tell my students: your background isn’t a barrier; it’s your foundation.”

While incarcerated in a maximum-security prison, Andrisse experienced the moment that shifted everything: the loss of his father to complications from Type 2 diabetes. He wasn’t able to say goodbye.

“That loss broke me open,” he recalls. His father’s struggle pushed him to pick up his first scientific article about diabetes. “Even though I was physically caged, my mind was free, roaming inside the human cell, trying to understand disease. That spark became my purpose.”

That moment changed the trajectory of his life and set him on a path toward science.

By the time he neared release, Andrisse saw education as the only pathway forward. He applied to six graduate programs. Five rejected him immediately. The sixth, Saint Louis University, accepted him after a mentor advocated on his behalf.

“That one ‘yes’ changed everything,” he says.

Andrisse earned his Ph.D. in Physiology and an MBA in Finance, finishing in just four years at the top of his class. Education wasn’t just a tool, he explains — it was transformative. “Education humanized me again. It helped me see myself as a thinker, a scientist, and a contributor.”

After experiencing the barriers of reentry firsthand, Andrisse founded From Prison Cells to Ph.D. (P2P), a national nonprofit that supports justice-impacted individuals pursuing higher education.

“When I was released, there was no clear roadmap for someone with my background,” he says. “Every door came with a lock and a label. I founded P2P to make sure others don’t have to navigate those barriers alone.”

The program has now supported over a thousand scholars, helping people move “from conviction to contribution.”

Andrisse is outspoken about how universities assess applicants with criminal records, and what they get wrong.

“Most institutions treat a criminal record as a permanent reflection of character rather than a snapshot of circumstance,” he says. “Second chances aren’t charity. They’re smart investments in human potential.”

To critics who view incarceration as a life sentence of stigma, he is unwavering: “Accountability matters, but so does access. Redemption isn’t about erasing mistakes — it’s about learning from them and using that experience to make a difference.”

Today, Andrisse’s work operates at the intersection of two worlds: molecular research and criminal justice reform. His lab focuses on diabetes, the disease that defined so much of his father’s life, while his advocacy pushes for policies that expand opportunity for others with stories like his.

“They intersect at the point of healing,” he says. “My lived experience makes me a more compassionate scientist, a more grounded educator, and a more relentless advocate.”

At Howard University, Andrisse is more than a faculty member. He is a symbol of persistence, a mentor to first-generation and underrepresented students, and a living argument for the power of redemption.

“I’m living proof that science and justice can inform one another,” he says. “That data and dignity can coexist.”

What was once unimaginable is now a reality, not only for him, but for the future scholars who see their own possibilities reflected in his story.

Photo Credit: Howard University